2. 苏州大学附属儿童医院重症医学科, 江苏 苏州 215025;

3. 苏州大学附属儿童医院感染管理科, 江苏 苏州 215025

2. Department of Pediatric Intensive Care Unit, Children's Hospital of Soochow University, Suzhou 215025, China;

3. Department of Infection Management, Children's Hospital of Soochow University, Suzhou 215025, China

腺病毒是急性社区呼吸道感染中常见的病原体,同样可以导致医院获得性感染,约占呼吸道病毒医院感染的6.0%~9.1%[1-2]。腺病毒医院感染多为散发,但也有报道[3-4]提示腺病毒曾造成眼科门诊和军队中的感染流行。临床工作中发现腺病毒医院感染更易导致危重症,目前对于腺病毒医院感染的系统报道很少。因此,本研究通过回顾性分析儿童腺病毒医院感染流行病学及临床特征,以明确需要保护的重点人群,为针对性的预防和治疗提供依据。

1 资料与方法 1.1 资料来源2011年1月—2020年12月苏州大学附属儿童医院收治的腺病毒感染患儿的病例资料。入院>48 h后呼吸道分泌物检出腺病毒为医院感染组,入院≤48 h呼吸道分泌物检出腺病毒为社区感染组。

1.2 诊断标准 1.2.1 腺病毒感染诊断标准[5](1) 发病前8 d内密切接触过腺病毒感染病例;(2)发热伴咽痛、干咳;(3)单侧或双侧颈部出现淋巴结肿大;(4)咽部充血、咽后壁淋巴滤泡增生、有点或片状灰白色分泌物覆于扁桃体表面;(5)外周血白细胞正常、升高或降低,分类淋巴细胞比例降低,单核细胞比例升高。符合以上条件者,临床诊断为腺病毒感染。若临床诊断病例同时具备以下任何一种实验室检查结果,则为腺病毒感染确诊病例:(1)咽拭子检测腺病毒特异性核酸阳性;(2)血清腺病毒特异性IgM抗体阳性。

1.2.2 医院感染诊断标准依据卫生部2001年颁发的《医院感染诊断标准(试行)》[6],有下列情况属于医院感染:(1)无明确潜伏期的感染,规定入院48 h后发生的感染为医院感染;有明确潜伏期的感染,自入院时起超过平均潜伏期后发生的感染为医院感染;(2)在原感染已知病原体基础上又分离出新的病原体(排除污染和原来的混合感染)的感染;(3)由于诊疗措施激活的潜在性感染。

1.2.3 重症肺炎的诊断标准参照《儿童社区获得性肺炎诊疗规范(2019年版)》[7],出现以下任何一项即可诊断为重症肺炎:(1)一般情况差;(2)拒食或脱水征;(3)存在意识障碍;(4)呼吸明显增快(婴儿呼吸>70次/min,年长儿呼吸>50次/min);(5)存在紫绀;(6)有呼吸困难,如有鼻翼煽动、三凹征;(7)肺浸润范围为多肺叶受累或≥2/3的肺;(8)存在胸腔积液;(9)脉搏血氧饱和度≤92%;(10)存在肺外并发症;(11)超高热,持续高热超过5 d。

1.3 研究方法 1.3.1 资料收集设计统一的表格收集患儿的一般资料(性别、年龄、基础疾病)、临床表现及体征、住院时间、治疗及转归(各种药物和呼吸机使用情况)、实验室辅助检查结果(血常规、尿常规、粪便常规、血气分析、血生化、凝血常规、心肌三项等)、影像学表现、病原学检验资料等。

1.3.2 标本采集及检测通过鼻咽拭子、支气管肺泡灌洗采集呼吸道分泌物标本。

通过直接免疫荧光法检测呼吸道常见病毒:呼吸道合胞病毒(RSV)、腺病毒、流感病毒A型、流感病毒B型、副流感病毒1、2、3型(Pinf1、Pinf2、Pinf3)。逆转录-聚合酶链式反应(RT-PCR)法测定鼻病毒、偏肺病毒和支原体;直接化学发光法肺炎支原体IgG、IgM,肺炎支原体IgG标本浓度≥36.0 AU/mL,肺炎支原体IgM(COI)≥1.1,判为阳性。细菌培养根据标本在培养基中革兰染色、生物化学反应、菌落特点和显微镜下形态等对细菌种类进行鉴别。

1.4 统计学方法应用SPSS 26.0软件进行数据分析。正态分布计量资料采用x±s表示,两组均数比较采用t检验;两组率的比较采用χ2检验和Fisher确切概率法;非正态分布计量数据采用四分位数法表示,均数比较采用非参数检验;P≤0.05为差异有统计学意义。

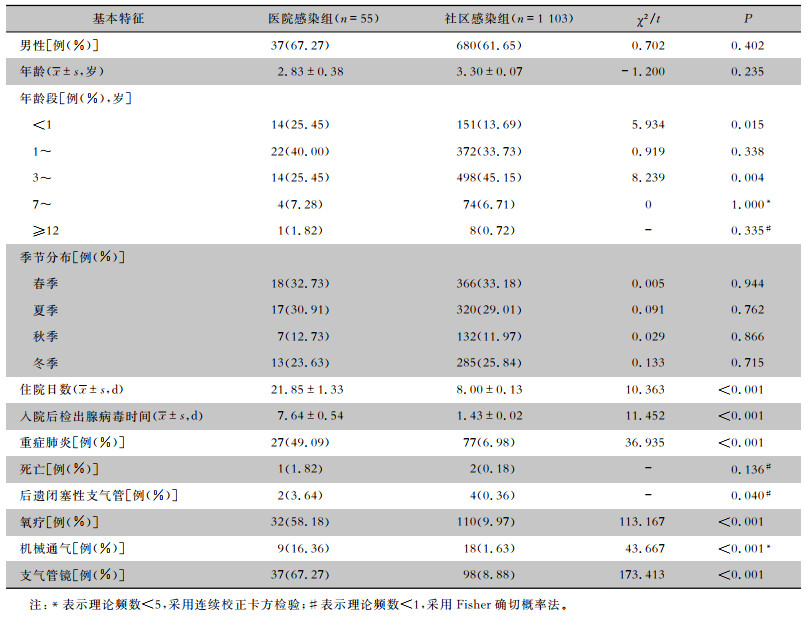

2 结果 2.1 基本特征2011年1月—2020年12月该儿童医院共收治腺病毒肺炎患儿1 158例,其中医院感染55例(4.75%),社区感染1 103例(95.25%)。55例医院感染组患儿平均年龄为(2.83±0.38)岁,男性37例(67.27%),主要发病年龄在3岁以下(36例,65.45%)。社区感染组患儿主要发病年龄为≥3岁且<7岁(498例,45.15%)。儿童腺病毒肺炎全年均可发生,医院感染组与社区感染组均以春夏季多见,其次多见于冬季。

医院感染组患儿在入院后(7.64±0.54)d检出腺病毒,社区感染组在(1.43±0.02)d检出;医院感染组患儿平均住院日数为(21.85±1.33)d,长于社区感染组的(8.00±0.13)d;医院感染组中49.09%的患儿发生重症肺炎,高于社区感染组的6.98%;医院感染组分别有58.18%、16.36%、67.27%的患儿接受氧疗、有创通气和支气管镜盥洗,高于社区感染组的9.97%、1.63%、8.88%;医院感染组3.64%后期发生闭塞性毛细支气管炎,高于社区感染组的0.36%;差异均有统计学意义(均P<0.05)。医院感染组患儿病死率为1.82%,社区感染组为0.18%。见表 1。

| 表 1 2011—2020年腺病毒感染儿童的基本特征 Table 1 Basic characteristics of children with adenovirus infection, 2011-2020 |

|

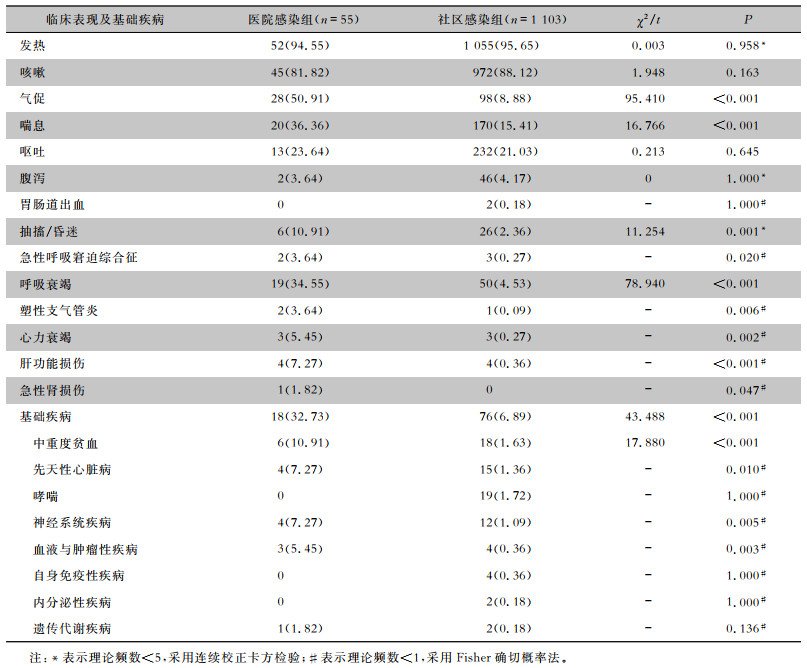

医院感染组有94.55%的患儿出现发热,发热日数为(10.80±0.93)d,高于社区感染组的(6.06±0.13)d,差异有统计学意义(t=5.034,P<0.001)。医院感染组患儿发生喘息(36.36%)、气促(50.91%)、抽搐/昏迷(10.91%)的比率均高于社区感染组的15.41%、8.88%、2.36%;医院感染组患儿发生急性呼吸窘迫综合征(3.64%)、塑性支气管炎(3.64%)、呼吸衰竭(34.55%)、心力衰竭(5.45%)、肝功能损伤(7.27%)和急性肾损伤(1.82%)的比率高于社区感染组的0.27%、0.09%、4.53%、0.27%、0.36%、0;差异均有统计学意义(均P<0.05)。

医院感染组中32.73%的患儿有基础疾病,高于社区感染组的6.89%;医院感染组患儿中中重度贫血(10.91%)、先天性心脏病(7.27%)、血液与肿瘤性疾病(5.45%)和神经系统疾病(7.27%,包括脑发育不良及脑积水3例、脑瘫1例)的比率均高于社区感染组的1.63%、1.36%、0.36%、1.09%,差异均有统计学意义(均P<0.05)。见表 2。

| 表 2 2011—2020年腺病毒感染儿童临床表现及基础疾病情况[例(%)] Table 2 Clinical manifestations and underlying diseases of children with adenovirus infection, 2011-2020 (No. of cases [%]) |

|

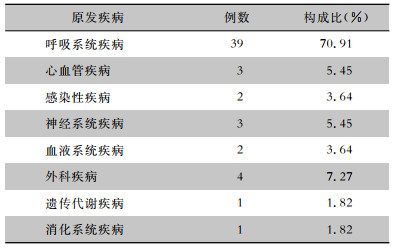

医院感染组患儿原发疾病以呼吸系统疾病最为多见,占70.91%,其次依次为外科疾病(7.27%)、心血管疾病(5.45%)、神经系统疾病(5.45%)、血液系统疾病(3.64%)、感染性疾病(3.64%)、遗传代谢疾病(1.82%)和消化系统疾病(1.82%)。见表 3。

| 表 3 2011—2020年55例腺病毒医院感染儿童原发疾病分布 Table 3 Distribution of primary diseases in 55 children with adenovirus HAI, 2011-2020 |

|

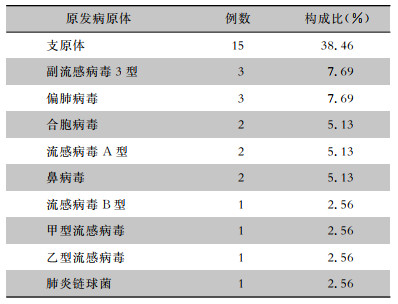

医院感染组39例呼吸系统疾病患儿中,原发感染病原体以支原体多见(38.46%),其次为副流感病毒3型(7.69%)、偏肺病毒(7.69%)、合胞病毒(5.13%)、流感病毒A型(5.13%)、鼻病毒(5.13%)、流感病毒B型(2.56%)、甲型流感病毒(2.56%)、乙型流感病毒(2.56%)、肺炎链球菌(2.56%)。见表 4。

| 表 4 2011—2020年腺病毒医院感染儿童呼吸系统原发病原体分布(n=39) Table 4 Distribution of primary pathogens of children with respiratory system adenovirus HAI, 2011-2020 (n=39) |

|

腺病毒发生医院感染与其生物学特征相关,腺病毒作为DNA病毒,在环境中相对稳定,可以通过大液滴传播,也可以通过小气溶胶液滴传播,从而导致婴幼儿社区获得性腺病毒肺炎的散发,甚至暴发[8-9]。在干燥的夏季,此类气溶胶仍然稳定,因此夏季腺病毒引起的下呼吸道感染相比其他病毒,如呼吸道合胞病毒和流感病毒均较多。腺病毒还可通过呼吸道分泌物和潜在的污染环境表面在封闭环境中迅速传播,从而导致医院内传播[10]。

本研究中腺病毒医院感染组中有49.09%的患儿为重症病例,婴幼儿为主,以发热、咳嗽等呼吸道感染为主要表现,发热日数明显延长,易出现气促、喘息及抽搐/昏迷等症状。这可能和感染患儿本身存在基础疾病相关,腺病毒感染可导致幼儿或免疫功能低下者的发病率和病死率高[11]。本研究发现,腺病毒医院感染组32.73%的患儿具有基础疾病,如先天性心脏病、中重度贫血、神经系统疾病(脑发育不良、脑瘫)、血液系统疾病和肿瘤。目前经批准获得许可的4型及7型腺病毒口服活疫苗只用于美国新兵,并没有获批在儿童和成人中普遍使用。已有研究使用复制缺陷型腺病毒载体构建了针对3、7、14和55型腺病毒的候选疫苗有望在未来推广[12-13],有研究[14]以11型腺病毒FK作为抗原制备了单克隆抗体显示出高效的中和病毒的作用,但是目前尚无临床可用的保护性抗体保护重点人群。因此,对于重点人群采取的保护措施仍然是传统的宣教、保护隔离等措施。

本研究中,原发呼吸道感染患儿更容易发生腺病毒医院感染,而呼吸道感染原发病原体中,以支原体感染多见(38.46%)。研究[15-16]表明,腺病毒感染更容易继发于肺炎支原体感染,并且机体同时感染腺病毒和肺炎支原体与单一病原体感染相比,临床表现和并发症更重,其原因可能为机体感染支原体及其他病原体后,由于原发病原的直接损伤及免疫炎性反应,影响了宿主局部及全身的免疫功能,导致体液及细胞免疫系统紊乱,更易出现腺病毒医院感染。也有研究[17]认为腺病毒医院感染可能由于呼吸道黏膜损伤、机体防御机能减弱、病原体进一步进入下呼吸道定植造成。气管插管、胃管和支气管镜等侵入性操作,可使呼吸道上皮受损,使病原体更容易黏附定植并进一步造成感染。

本研究通过比较腺病毒医院感染和社区感染,发现腺病毒是儿童医院感染的重要病毒病原体,具有发生年龄小,发热和住院时间更长,累及更多器官功能受损的特点,并且其发病和部分基础疾病有关,如中重度贫血、先天性心脏病和神经系统疾病等,腺病毒医院感染也会继发于急性呼吸道感染,最多见于肺炎支原体感染后。临床工作中应进一步确定重点保护人群,严格做好防护,以减少腺病毒医院感染的发生。

利益冲突:所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突。

| [1] |

Choi HS, Kim MN, Sung H, et al. Laboratory-based surveillance of hospital-acquired respiratory virus infection in a tertiary care hospital[J]. Am J Infect Control, 2017, 45(5): e45-e47. DOI:10.1016/j.ajic.2017.01.009 |

| [2] |

Spaeder MC, Fackler JC. Hospital-acquired viral infection increases mortality in children with severe viral respiratory infection[J]. Pediatr Crit Care Med, 2011, 12(6): e317-e321. DOI:10.1097/PCC.0b013e3182230f6e |

| [3] |

Russell KL, Hawksworth AW, Ryan MAK, et al. Vaccine-preventable adenoviral respiratory illness in US military recruits, 1999-2004[J]. Vaccine, 2006, 24(15): 2835-2842. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.12.062 |

| [4] |

James L, Vernon MO, Jones RC, et al. Outbreak of human adenovirus type 3 infection in a pediatric long-term care facility-Illinois, 2005[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2007, 45(4): 416-420. DOI:10.1086/519938 |

| [5] |

全军传染病专业委员会, 新突发传染病中西医临床救治课题组. 腺病毒感染诊疗指南[J]. 解放军医学杂志, 2013, 38(7): 529-534. Special Committee of Infectious Diseases of PLA, Research Group of Clinical Treatment of New Emergent Infectious Diseases by Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of adenovirus infections[J]. Medical Journal of Chinese People's Liberation Army, 2013, 38(7): 529-534. |

| [6] |

中华人民共和国卫生部. 医院感染诊断标准(试行)[J]. 中华医学杂志, 2001, 81(5): 314-320. Ministry of Health of the People's Republic of China. Diagnostic criteria for nosocomial infections(proposed)[J]. National Medical Journal of China, 2001, 81(5): 314-320. DOI:10.3760/j:issn:0376-2491.2001.05.027 |

| [7] |

中华人民共和国国家卫生健康委员会, 国家中医药局. 儿童社区获得性肺炎诊疗规范(2019年版)[J]. 中华临床感染病杂志, 2019, 12(1): 6-13. National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China, State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Guideline for diagnosis and treatment of community-acquired pneumonia in children (2019 version)[J]. Chinese Journal of Clinical Infectious Diseases, 2019, 12(1): 6-13. |

| [8] |

Lee E, Kim CH, Lee YJ, et al. Annual and seasonal patterns in etiologies of pediatric community-acquired pneumonia due to respiratory viruses and Mycoplasma pneumoniae requiring hospitalization in South Korea[J]. BMC Infect Dis, 2020, 20(1): 132. DOI:10.1186/s12879-020-4810-9 |

| [9] |

Chowdhury F, Shahid ASMSB, Ghosh PK, et al. Viral etiology of pneumonia among severely malnourished under-five children in an urban hospital, Bangladesh[J]. PLoS One, 2020, 15(2): e0228329. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0228329 |

| [10] |

Russell KL, Broderick MP, Franklin SE, et al. Transmission dynamics and prospective environmental sampling of adenovirus in a military recruit setting[J]. J Infect Dis, 2006, 194(7): 877-885. DOI:10.1086/507426 |

| [11] |

Lynch JP 3rd, Kajon AE. Adenovirus: epidemiology, global spread of novel serotypes, and advances in treatment and prevention[J]. Semin Respir Crit Care Med, 2016, 37(4): 586-602. DOI:10.1055/s-0036-1584923 |

| [12] |

Liu TT, Zhou ZC, Tian XG, et al. A recombinant trivalent vaccine candidate against human adenovirus types 3, 7, and 55[J]. Vaccine, 2018, 36(16): 2199-2206. DOI:10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.02.050 |

| [13] |

Tian XG, Jiang ZX, Fan Y, et al. A tetravalent vaccine comprising hexon-chimeric adenoviruses elicits balanced protective immunity against human adenovirus types 3, 7, 14 and 55[J]. Antiviral Res, 2018, 154: 17-25. DOI:10.1016/j.antiviral.2018.04.001 |

| [14] |

Tian XG, Fan Y, Liu ZW, et al. Broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibodies against human adenovirus types 55, 14p, 7, and 11 generated with recombinant type 11 fiber knob[J]. Emerg Microbes Infect, 2018, 7(1): 206. |

| [15] |

靳丹丹, 周卫芳, 李嫣, 等. 儿童腺病毒肺炎的混合感染特点和重症病例的危险因素分析[J]. 临床肺科杂志, 2019, 24(10): 1747-1750. Jin DD, Zhou WF, Li Y, et al. Characteristics of mixed infection of adenovirus pneumonia in children and risk factors of severe cases[J]. Journal of Clinical Pulmonary Medicine, 2019, 24(10): 1747-1750. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1009-6663.2019.10.001 |

| [16] |

Lion T. Adenovirus infections in immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients[J]. Clin Microbiol Rev, 2014, 27(3): 441-462. DOI:10.1128/CMR.00116-13 |

| [17] |

Ahmed AH, Thongprayoon C, Schenck LA, et al. Adverse in-hospital events are associated with increased in-hospital mortality and length of stay in patients with or at risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome[J]. Mayo Clin Proc, 2015, 90(3): 321-328. |