2. 南京医科大学附属淮安第一医院麻醉科, 江苏 淮安 223300

2. Department of Anesthesiology, The Affiliated Huai'an Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Huai'an 223300, China

随着现代医学的发展,广谱抗菌药物、糖皮质激素、免疫抑制剂频繁使用,介入治疗、放射治疗、化学治疗,以及侵入性操作,如中心静脉置管(central venous catheter, CVC)、机械通气、血液透析、体外循环/体外膜肺氧合(ECMO)等增多,念珠菌血症(candidemia)成为全球医院侵袭性真菌感染的常见类型。研究[1-3]显示,念珠菌感染已跃居医院血流感染病原菌第四位,其住院患者发病率及病死率逐年上升[4-6]。念珠菌血症患者早期全身毒血症症状较轻,临床症状和体征无特异性,病程进展常缓慢,易被原发病或伴发的其他感染所掩盖[7],其病原菌分布有明显地域差异,不同地区和医院之间,乃至不同科室间的流行病学特点和临床特征可能有很大差别[8-9]。因此,本研究对淮安市某医院念珠菌血症的病原菌分布、菌株耐药情况、患者临床资料、医院感染情况进行分析和探讨,建立并应用标准化医院感染干预模型,以期为减少念珠菌血症医院感染提供参考和帮助。

1 资料与方法 1.1 资料 1.1.1 资料来源选取淮安市某医院2015年1月—2019年12月507 974例住院患者作为对照组,2020年1月—2022年12月392 616例住院患者作为干预组。2015年1月—2022年12月血培养分离出念珠菌且临床诊断为念珠菌血症的患者共181例,其中对照组117例,干预组64例,收集其临床资料和医院感染情况。根据2016年美国传染病协会(IDSA)《念珠菌病临床实践指南》[10]《中国成人念珠菌病诊断与治疗专家共识》[7]及卫生部发布的《医院感染诊断标准(试行)》[11]相关标准诊断患者,并纳入血培养阳性的第1株念珠菌,剔除同一患者来源的重复菌株。本研究属回顾性研究,符合医学伦理学标准,经医院伦理委员会审查豁免知情同意。

1.1.2 仪器和试剂BACTEC FX全自动血培养仪(美国BD公司),VITEK 2 Compact微生物鉴定及药物敏感性(药敏)分析系统和VITEK MS质谱监测系统(法国生物梅里埃公司),DL-96A细菌鉴定及药敏分析系统(珠海迪尔生物工程有限公司),沙保罗琼脂平板(郑州安图生物工程股份有限公司),YST ID鉴定卡和ATB Fungus 3酵母样真菌药敏试验盒(法国生物梅里埃公司),杏林医院感染实时监控系统(杭州杏林信息科技有限公司),LIS 6.0实验室监测系统(上海卫宁健康科技集团股份有限公司)。

1.2 方法 1.2.1 培养鉴定及药敏试验菌株培养鉴定严格按照《全国临床检验操作规程》(第4版)[12]进行。药敏试验方法、流程和判断标准参照美国临床实验室标准化协会(CLSI)M27(2017)文件[13];临床折点、流行病学界值(epidemiological cut-off values, ECVs)分别参照CLSI M59(2018)、M60(2017)文件[14-15],氟康唑耐药EVCs为≥64 μg/mL,伊曲康唑耐药EVCs为≥1 μg/mL,伏立康唑耐药EVCs为≥4 μg/mL,氟胞嘧啶耐药EVCs为≥32 μg/mL,两性霉素B耐药EVCs为≥8 μg/mL。

1.2.2 医院感染监测及相关率的计算方法医院感染病例监测应用杏林医院感染实时监控系统,个案调查参考国家卫生健康委员会发布的WS/T 524—2016《医院感染暴发控制指南》[16]中“(疑似)医院感染病例个案调查”。血培养检出病原菌的阳性率=血培养出病原菌标本份数/血培养送检标本份数×100%;念珠菌检出率=血培养检出念珠菌株数/血培养检出病原菌株数×100%;念珠菌血症发病率=念珠菌血症感染患者例数/住院患者例数×100%;念珠菌血症医院感染率=念珠菌血症医院感染患者例数/住院患者例数×100%。

1.2.3 干预措施对照组实施常规医院感染控制措施,包括病例监测(杏林医院感染实时监控系统病例预警)、标准预防(正确手卫生,个人防护,隔离措施如限制患者转运及器械设备专人专用、优先清洁、消毒、减少侵入性装置使用等)和风险评估。

干预组执行符合该院情况的标准化干预措施。(1)主动监测念珠菌检出及感染情况:与微生物室直接对接,利用信息系统预警念珠菌血症聚集,并由临床感染控制医生进行病例监测及感染情况分析;(2)除标准预防措施外,利用信息系统抓取血流感染相关危险因素,针对危险因素强化干预措施,包括但不限于加强血管导管维护、缩短血管导管留置时间、合理使用抗菌药物及糖皮质激素、尽早肠内营养等;(3)针对病区环境开展同质化措施,包括强化宣教(夏季提前对全院进行提醒)、监测温湿度(安装温湿度仪,保证湿度<60%)、降低空气中念珠菌孢子浓度(通风、使用干燥剂或除湿机、消毒);(4)对控制效果进行持续跟踪评价。

1.2.4 统计学方法应用SPSS 23.0软件(美国IBM公司)进行数据分析,计量资料采用t检验,计数资料采用χ2检验,P≤0.05为差异有统计学意义。

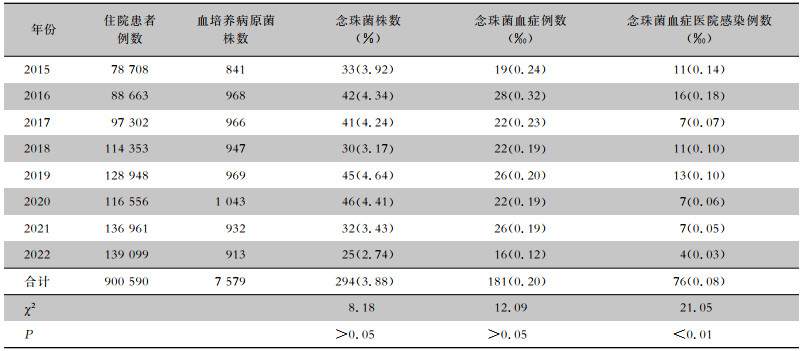

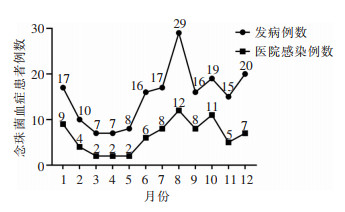

2 结果 2.1 念珠菌血症患者一般资料、发病率及检出率2015年1月—2022年12月该院住院患者共送检血培养101 234份,其中7 579份检出病原菌,且每份均检出1株菌,共检出7 579株病原菌,阳性率为7.49%。181例患者共检出念珠菌294株,检出率为3.88%,总发病率为0.20‰。见表 1。其中,男性患者110例(60.77%),女性患者71例(39.23%),平均年龄(59.09±19.80)岁。念珠菌血症医院感染患者76例(0.08‰),均排除混合感染,其中,男性47例(61.84%),女性29例(38.16%),平均年龄(58.13±22.06)岁。2015—2022年间,该院念珠菌检出量夏季最高,念珠菌血症医院感染聚集主要发生在1月及7—10月。见图 1。对照组中念珠菌血症117例,发病率为0.23‰,医院感染58例,医院感染发病率为0.11‰;干预组中念珠菌血症64例,发病率为0.11‰,医院感染18例,医院感染发病率为0.05‰;两组患者念珠菌血症发病率、医院感染发病率比较,差异均有统计学意义(χ2值分别为4.994、12.524,均P<0.05)。

| 表 1 2015—2022年该院念珠菌血症发生情况 Table 1 Occurrence of candidemia in the hospital from 2015 to 2022 |

|

|

| 图 1 2015—2022年念珠菌血症与季节的关系 Figure 1 Relationship between the occurrence of candidemia and seasons from 2015 to 2022 |

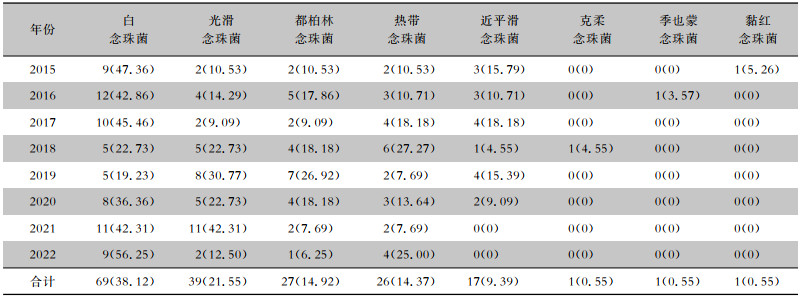

181例念珠菌血症患者的标本共分离白念珠菌69株(38.12%),光滑念珠菌39株(21.55%),都柏林念珠菌27株(14.92%),热带念珠菌26株(14.37%),近平滑念珠菌17株(9.39%),以及克柔念珠菌、季也蒙念珠菌、黏红念珠菌各1株(各0.55%)。见表 2。不同年份菌株分布比较,差异无统计学意义(χ2=35.89, P=0.145)。

| 表 2 2015—2022年医院念珠菌血症菌种分布[株(%)] Table 2 Species distribution of Candida in the hospital from 2015 to 2022 (No. of isolates [%]) |

|

76例念珠菌血症医院感染患者中,感染白念珠菌23例(30.26%),光滑念珠菌12例(15.79%),都柏林念珠菌13例(17.10%),热带念珠菌15例(19.74%),近平滑念珠菌11例(14.47%),季也蒙念珠菌、黏红念珠菌各1例(各1.32%)。

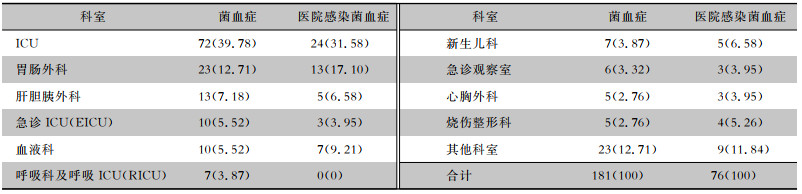

2.2.2 念珠菌血症病原菌科室分布情况多数念珠菌血症患者来自重症监护病房(ICU)和外科,其中ICU(39.78%)、胃肠外科(12.71%)和肝胆胰外科(7.18%)为发生念珠菌血症的主要临床科室。念珠菌血症医院感染患者主要分布于ICU(31.58%)、胃肠外科(17.10%)、血液科(9.21%)、新生儿科(6.58%)及肝胆外科(6.58%)。见表 3。发生念珠菌血症医院感染患者的科室分布比较,差异有统计学意义(χ2=32.38, P=0.009)。

| 表 3 念珠菌血症患者的临床科室分布[例(%)] Table 3 Clinical department distribution of patients with candidemia (No. of cases [%]) |

|

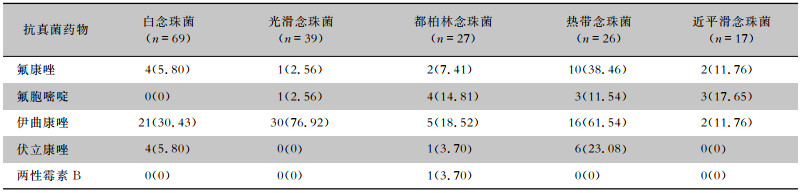

热带念珠菌对氟康唑、伊曲康唑、伏立康唑耐药率较高,分别为38.46%、61.54%、23.08%;白念珠菌、光滑念珠菌对伊曲康唑的耐药率较高,分别为30.43%、76.92%。见表 4。

| 表 4 2015—2022年念珠菌血症病原菌耐药情况[株(%)] Table 4 Antimicrobial resistance of candidemia-originated Candida from 2015 to 2022 (No. of isolates [%]) |

|

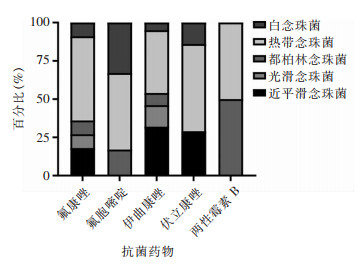

念珠菌血症医院感染菌株耐药情况见图 2。热带念珠菌医院感染株对各类抗真菌药耐药比例均较高,与白念珠菌医院感染株比较,两者对氟康唑及氟胞嘧啶耐药率差异有统计学意义(χ2=5.353,P=0.039;χ2=5.363,P=0.047);与都柏林念珠菌、近平滑念珠菌医院感染株比较,对伊曲康唑耐药差异均有统计学意义(χ2=5.812,P=0.016;χ2=4.965,P=0.026);与光滑念珠菌医院感染株比较,对各类药物的耐药差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。

|

| 图 2 医院感染念珠菌血症菌株耐药情况 Figure 2 Antimicrobial resistance of Candida from HAI-associated candidemia |

2015—2022年该院住院患者中念珠菌血症死亡患者11例(6.08%),医院感染念珠菌血症死亡患者6例(7.89%)。

3 讨论念珠菌在人体内分布广泛,主要定植于胃肠道、呼吸道、泌尿生殖道和皮肤[17],可通过接触污染的环境表面和设备传播,或在患者间传播。作为条件致病菌,念珠菌通常由于正常菌群的浓度和分布发生变化,以及黏膜屏障功能遭受破坏而引起感染。念珠菌血症是念珠菌侵袭性感染中最常见的类型,发病率不断增高。2015—2022年间该院住院患者念珠菌血症发病率为0.12‰~0.32‰,与国内外报道[18-19]一致。念珠菌检出数量波动变化,不同年份医院感染菌株情况统计显示,白念珠菌居首位,与中国医院侵袭性真菌病监测网(China hospital invasive fungal surveillance net, CHIF-NET)数据相符[20]。念珠菌血症菌群的科室分布有差异(P=0.009)[8-9]。该院常见菌株对两性霉素B及伏立康唑敏感度较高,与国内外研究[7, 20-21]结果一致,但该院分离菌株对伊曲康唑耐药性较高,且热带念珠菌的耐药性高于相关报道[22-24]的7.1%~19.3%。念珠菌血症病死率较高,无特异临床表现,其诊断依赖血培养,通过微生物学方法明确致病菌种及其药敏结果耗时较长,而其他诊断手段如血清学[G试验、GM试验及降钙素原(PCT)等]和分子生物学检测均不具备独立诊断价值,不利于早期诊断及干预,因此,早期干预医院感染念珠菌血症十分必要[5, 7, 25-27]。

念珠菌血症的危险因素较多,有研究[28-29]将主要危险因素归为使用广谱抗菌药物、CVC、全胃肠外营养、透析、腹部大手术、糖皮质激素或其他免疫抑制剂的使用,其灵敏度为84%、特异度为60%,阴性预测值高达99%。该院监测发现近平滑念珠菌是近年来念珠菌血症的主要菌种之一。研究[30]显示近平滑念珠菌可在血管导管内形成生物膜,增强菌株毒力。因此,该院持续做好血管导管管理工作,包括:提高手卫生依从性,严格遵守无菌操作原则,加强CVC管道维护,以及缩短留置CVC时间[31]。

统计发现7—10月份是该院念珠菌血症医院感染的高峰,病例聚集亦发生在8月。文献[6, 27, 32]报道夏秋季空气中真菌负荷大,故可能与夏秋季念珠菌感染高发有关。由于环境限制,该院治疗室和库房普遍通风不良,念珠菌孢子易在空气中悬浮,沉积后黏附于物体表面,科内库房和治疗室物体表面霉斑最多。该院1月份念珠菌血流感染患者较多,可能也与通风不良有关。因此,夏季提前进行强化宣教,安装温湿度仪监测环境温湿度,采用通风、除湿、消毒等措施降低空气中孢子浓度应成为该院各科室常规工作。

该院感染管理部门根据文献检索和统计分析结果建立标准化医院感染干预模型,经过三年应用,念珠菌血症发病例数及医院感染例数下降且有统计学意义(P<0.01)。近两年无医院近平滑念珠菌血症发生,念珠菌血症患者的病死率及医院感染念珠菌血症患者病死率均低于相关报道[5, 27, 33-34]。因此,建立标准化医院感染干预模型,进行同质化的医院感染干预措施,对减少念珠菌血症医院感染具有重要意义。

本研究不足之处在于:由于医院感染监测信息系统不完善,该院2019年以前医院感染干预措施以纸质化记录为主,有缺失可能,无法量化干预措施并统计分析;此外,因试剂限制,未进行棘白菌素类药物的药敏试验。

利益冲突:所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突。

| [1] |

Wisplinghoff H, Bischoff T, Tallent SM, et al. Nosocomial bloodstream infections in US hospitals: analysis of 24, 179 cases from a prospective nationwide surveillance study[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2004, 39(3): 309-317. DOI:10.1086/421946 |

| [2] |

Kullberg BJ, Arendrup MC. Invasive candidiasis[J]. N Engl J Med, 2015, 373(15): 1445-1456. DOI:10.1056/NEJMra1315399 |

| [3] |

吴昌德, 郭凤梅, 邱海波. 中国ICU患者侵袭性念珠菌感染现状[J]. 中国医刊, 2018, 53(6): 585-587. Wu CD, Guo FM, Qiu HB. Current status of invasive candidal infection in Chinese ICU patients[J]. Chinese Journal of Medicine, 2018, 53(6): 585-587. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1008-1070.2018.06.002 |

| [4] |

Soulountsi V, Schizodimos T, Kotoulas SC. Deciphering the epidemiology of invasive candidiasis in the intensive care unit: is it possible?[J]. Infection, 2021, 49(6): 1107-1131. DOI:10.1007/s15010-021-01640-7 |

| [5] |

Koehler P, Stecher M, Cornely OA, et al. Morbidity and mortality of candidaemia in Europe: an epidemiologic Meta-analysis[J]. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2019, 25(10): 1200-1212. DOI:10.1016/j.cmi.2019.04.024 |

| [6] |

Wang H, Xu YC, Hsueh PR. Epidemiology of candidemia and antifungal susceptibility in invasive Candida species in the Asia-Pacific region[J]. Future Microbiol, 2016, 11: 1461-1477. DOI:10.2217/fmb-2016-0099 |

| [7] |

中国成人念珠菌病诊断与治疗专家共识组. 中国成人念珠菌病诊断与治疗专家共识[J]. 中国医学前沿杂志(电子版), 2020, 12(1): 35-50. Chinese Adult Candidiasis Diagnosis and Management Expert Consensus Group. Chinese consensus on the diagnosis and management of adult candidiasis[J]. Chinese Journal of the Frontiers of Medical Science(Electronic Version), 2020, 12(1): 35-50. |

| [8] |

Yapar N. Epidemiology and risk factors for invasive candidiasis[J]. Ther Clin Risk Manag, 2014, 10: 95-105. |

| [9] |

Magill SS, Edwards JR, Bamberg W, et al. Multistate point-prevalence survey of health care-associated infections[J]. N Engl J Med, 2014, 370(13): 1198-1208. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1306801 |

| [10] |

Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of candidiasis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2016, 62(4): e1-e50. DOI:10.1093/cid/civ933 |

| [11] |

中华人民共和国卫生部. 医院感染诊断标准(试行)[J]. 中华医学杂志, 2001, 81(5): 314-320. Department of Health of the People's Republic of China. Dia-gnostic criteria for nosocomial infections(proposed)[J]. National Medical Journal of China, 2001, 81(5): 314-320. DOI:10.3760/j:issn:0376-2491.2001.05.027 |

| [12] |

尚红, 王毓三, 申子瑜. 全国临床检验操作规程[M]. 4版. 北京: 人民卫生出版社, 2015: 783-899. Shang H, Wang YS, Shen ZY. National guide to clinical laboratory procedures[M]. 4th ed. Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House, 2015: 783-899. |

| [13] |

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. M27 reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts. 4th edition[EB/OL]. (2017-11-30)[2023-02-17]. https://clsi.org/standards/products/microbiology/documents/m27/.

|

| [14] |

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. M59 epidemiologi-cal cutoff values for antifungal susceptibility testing. 2nd edition[EB/OL]. (2018-01-12)[2023-02-17]. https://community.clsi.org/media/1934/m59ed2_sample-updated.pdf.

|

| [15] |

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. M60 performance standards for antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts. 1st edition[EB/OL]. (2017-11-30)[2023-02-17]. https://clsi.org/media/1895/m60ed1_sample.pdf.

|

| [16] |

中华人民共和国国家卫生和计划生育委员会. 医院感染暴发控制指南: WS/T 524—2016[S]. 北京: 中国标准出版社, 2017. National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People's Republic of China. Guideline of control of healthcare associated infection outbreak: WS/T 524-2016[S]. Beijing: China Standards Publishing House, 2017. |

| [17] |

Underhill DM, Iliev ID. The mycobiota: interactions between commensal fungi and the host immune system[J]. Nat Rev Immunol, 2014, 14(6): 405-416. DOI:10.1038/nri3684 |

| [18] |

Lockhart SR, Etienne KA, Vallabhaneni S, et al. Simultaneous emergence of multidrug-resistant Candida auris on 3 continents confirmed by whole-genome sequencing and epidemiological analyses[J]. Clin Infect Dis, 2017, 64(2): 134-140. DOI:10.1093/cid/ciw691 |

| [19] |

Zheng YJ, Xie T, Wu L, et al. Epidemiology, species distribution, and outcome of nosocomial Candida spp. bloodstream infection in Shanghai: an 11-year retrospective analysis in a tertiary care hospital[J]. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob, 2021, 20(1): 34. DOI:10.1186/s12941-021-00441-y |

| [20] |

Xiao M, Sun ZY, Kang M, et al. Five-year national surveillance of invasive candidiasis: species distribution and azole susceptibility from the China hospital invasive fungal surveillance net (CHIF-NET) study[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 2018, 56(7): e00577-18. |

| [21] |

Perlin DS, Rautemaa-Richardson R, Alastruey-Izquierdo A. The global problem of antifungal resistance: prevalence, mechanisms, and management[J]. Lancet Infect Dis, 2017, 17(12): e383-e392. DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30316-X |

| [22] |

Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ, Turnidge JD, et al. Twenty years of the SENTRY antifungal surveillance program: results for Candida species from 1997-2016[J]. Open Forum Infect Dis, 2019, 6(Suppl 1): S79-S94. |

| [23] |

Liu W, Tan JW, Sun JM, et al. Invasive candidiasis in intensive care units in China: in vitro antifungal susceptibility in the China-SCAN study[J]. J Antimicrob Chemother, 2014, 69(1): 162-167. DOI:10.1093/jac/dkt330 |

| [24] |

Xiao M, Fan X, Chen SCA, et al. Antifungal susceptibilities of Candida glabrata species complex, Candida krusei, Candida parapsilosis species complex and Candida tropicalis causing invasive candidiasis in China: 3 year national surveillance[J]. J Antimicrob Chemother, 2015, 70(3): 802-810. DOI:10.1093/jac/dku460 |

| [25] |

Murri R, Camici M, Posteraro B, et al. Performance evaluation of the (1, 3)-β-D-glucan detection assay in non-intensive care unit adult patients[J]. Infect Drug Resist, 2019, 12: 19-24. |

| [26] |

Mikulska M, Giacobbe DR, Furfaro E, et al. Lower sensitivity of serum (1, 3)-β-D-glucan for the diagnosis of candidaemia due to Candida parapsilosis[J]. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2016, 22(7): 646. |

| [27] |

Ala-Houhala M, Valkonen M, Kolho E, et al. Clinical and microbiological factors associated with mortality in candidemia in adult patients 2007-2016[J]. Infect Dis (Lond), 2019, 51(11/12): 824-830. |

| [28] |

Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Sable C, Sobel J, et al. Multicenter retro-spective development and validation of a clinical prediction rule for nosocomial invasive candidiasis in the intensive care setting[J]. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis, 2007, 26(4): 271-276. DOI:10.1007/s10096-007-0270-z |

| [29] |

Hermsen ED, Zapapas MK, Maiefski M, et al. Validation and comparison of clinical prediction rules for invasive candidiasis in intensive care unit patients: a matched case-control study[J]. Crit Care, 2011, 15(4): R198. DOI:10.1186/cc10366 |

| [30] |

Clark TA, Slavinski SA, Morgan J, et al. Epidemiologic and molecular characterization of an outbreak of Candida parapsilosis bloodstream infections in a community hospital[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 2004, 42(10): 4468-4472. |

| [31] |

O'Grady NP, Alexander M, Burns LA, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections[J]. Am J Infect Control, 2011, 39(4 Suppl 1): S1-S34. |

| [32] |

Giacobbe DR, Maraolo AE, Simeon V, et al. Changes in the relative prevalence of candidaemia due to non-albicans Candida species in adult in-patients: a systematic review, Meta-analysis and Meta-regression[J]. Mycoses, 2020, 63(4): 334-342. |

| [33] |

Barchiesi F, Orsetti E, Gesuita R, et al. Epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and outcome of candidemia in a tertiary refe-rral center in Italy from 2010 to 2014[J]. Infection, 2016, 44(2): 205-213. |

| [34] |

Choi H, Kim JH, Seong H, et al. Changes in the utilization patterns of antifungal agents, medical cost and clinical outcomes of candidemia from the health-care benefit expansion to include newer antifungal agents[J]. Int J Infect Dis, 2019, 83: 49-55. |