Clinical distribution characteristics and changing trend of postoperative pneumonia, 2014-2023

-

摘要:

目的 分析手术后肺炎临床分布特点及变化趋势, 为手术后肺炎的进一步监测和管理提供依据。 方法 收集南京医科大学第一附属医院2014—2023年手术后肺炎患者的临床资料, 回顾性分析手术后肺炎发病率、呼吸机相关肺炎(VAP)占比变化趋势及手术后肺炎发生时间和病原体分布, 以及各科室手术后肺炎发病率。 结果 2014—2023年全院共有653 609例患者接受外科手术, 手术例次数为676 245次, 其中有2 934例次发生手术后肺炎, 手术后肺炎发病率为0.43%。手术后肺炎患者平均年龄为(59.76±16.53)岁, 男性占比68.58%;手术后肺炎发病率由2014年的2.00% 降至2023年的0.10%, VAP占比由2014年的9.92%上升至2023年的99.10%, 差异均有统计学意义(均P<0.001)。手术后肺炎发生在术后7、10、30 d内的分别占65.81%、78.80%、95.64%, 发生率居前三的科室分别为心脏大血管外科(5.277%)、神经外科(2.114%)和胸外科(1.130%); 感染病原体以革兰阴性菌为主(77.58%)。 结论 手术后肺炎发病率呈下降趋势, 其中VAP患者应作为后续改进工作的重点关注对象, 心脏血管外科、神经外科和胸外科则是手术后肺炎的重点关注科室, 手术后10 d内应作为手术后肺炎的重点关注时间段。 Abstract:Objective To analyze the clinical distribution characteristics and changing trend of postoperative pneumonia (POP), and provide basis for further monitoring and management of POP. Methods Clinical data of POP patients in the First Affiliated Hospital with Nanjing Medical University from 2014-2023 were collected. The incidence of POP, the changing trend of proportion of ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), the occurrence time, pathogen distribution, and incidence of POP in various departments were analyzed retrospectively. Results From 2014 to 2023, a total of 653 609 patients in the hospital received surgery, with 676 245 times of operations, out of which 2 934 cases had POP, and the incidence of POP was 0.43%. The average age of POP patients was (59.76±16.53) years old, with 68.58% being male. The incidence of POP decreased from 2.00% in 2014 to 0.10% in 2023, and the proportion of VAP increased from 9.92% in 2014 to 99.10% in 2023, with statistically significant differences (all P < 0.001). POP occurred within 7, 10, and 30 days after surgery accounted for 65.81%, 78.80%, and 95.64%, respectively. The top three departments with the highest incidences were cardiovascular surgery (5.277%), neurosurgery (2.114%), and thoracic surgery (1.130%). The main pathogen of infection was Gram-negative bacteria (77.58%). Conclusion The incidence of POP shows a downward trend. VAP patients should be the focus of follow-up improvement work. Departments of cardiovascular surgery, neurosurgery, and thoracic surgery are the key departments of POP, and 10 days after surgery should be the critical period of POP. -

手术后肺炎(postoperative pneumonia, POP)是外科手术常见的术后并发症和医院感染类型,发病率约占所有医院获得性肺炎的50%[1],可能导致患者原有疾病治疗难度增加,影响患者各项预后指标,降低生命质量甚至导致死亡[2-3]。同时还将增加患者再住院率和非计划手术率,延长住院日数,增加住院相关费用[4-5]。外科手术患者POP导致住院费用平均增加约为23 768.7元,高于术后其他医院感染类型[6]。与非POP相比,POP患者病死率更高,达10%~30%[7-8]。2024年4月国家卫生健康委医院管理研究所下发了“夯实围术期感染防控,保障手术质量安全”(“感术”行动)实施方案,要求将POP发病率逐步降低作为行动完成性监测指标。本研究通过全面回顾南京医科大学某附属医院2014—2023年POP临床分布特点及变化趋势,以期为POP进一步的监测和管理提供方向和依据,现报告如下。

1. 对象与方法

1.1 研究对象

选取南京医科大学某附属医院2014—2023年所有POP患者。纳入标准:(1)入院时间大于48 h;(2)住院期间进行手术且发生POP。本研究已通过该院医学伦理审批。

1.2 研究方法

通过杏林医院感染实时监测系统调取2014—2023年POP患者临床资料,回顾性分析POP患者基本情况,POP发病率、呼吸机相关肺炎(ventilator-associated pneumonia, VAP)占比变化趋势及POP发生时间和病原体分布,以及各科室POP发病率。统计POP感染病原体时,剔除同一患者相同标本重复分离菌株。

1.2.1 POP判定标准

POP判定标准参照“感术”行动相关要求,本研究将POP定义为患者手术结束到出院期间发生的医院获得性肺炎。肺炎诊断标准依据卫生部2001年颁布的《医院感染诊断标准(试行)》[9]和2018年发布的《术后肺炎预防和控制专家共识》[10]中POP判断标准。

1.2.2 计算公式

参照“感术”行动中计算公式,POP发病率=住院患者手术后新发生肺炎例次数/同期住院患者手术例次数×100%;VAP占比=POP患者中VAP例次数/所有POP患者例次数×100%。

1.2.3 POP发生科室和发生时间界定

POP发生科室以手术时所在科室为准;POP发生时间=POP诊断时间-手术结束时间。

1.3 统计分析

应用WPS 2023整理数据,应用SPSS 21.0软件对数据进行统计分析,计数资料以例数或百分率(%)表示,采用卡方(χ2)检验进行组间比较和趋势分析,P≤0.05为差异具有统计学意义。

2. 结果

2.1 基本情况

2014—2023年全院共有653 609例患者接受外科手术,手术例次数为676 245次,其中有2 934例患者发生POP,POP发病率为0.43%;POP患者中,男性占68.58%,女性占31.42%;年龄为(59.76±16.53)岁,以择期手术为主(75.36%),国家医院感染监测(NNIS)风险指数以1分为主(44.20%)。见表 1。

表 1 2014—2023年2 934例POP患者基本情况Table 1 Basic information of 2 934 POP patients, 2014-2023基本情况 患者例数 构成比(%) 年龄(岁) <50 615 20.96 50~59 573 19.53 60~69 914 31.15 ≥70 832 28.36 性别 男性 2 012 68.58 女性 922 31.42 手术方式 急诊 723 24.64 择期 2 211 75.36 NNIS风险指数(分) 0 577 19.67 1 1 297 44.20 2 1 045 35.62 3 15 0.51 2.2 POP发病率及VAP占比变化趋势

2014—2023年POP发病率为0.10%~2.00%,呈下降趋势(χ2=43 96.50,P<0.001)。2 934例POP中,有1 158例为VAP,VAP占比达39.47%,且VAP占比由2014年的9.92%上升至2023年的99.10%,呈上升趋势(χ2=1 735.2,P<0.001)。见表 2。

表 2 2014—2023年POP发病率及VAP占比Table 2 Changing trend of POP incidence and proportion of VAP, 2014-2023年份 手术例次数 POP例次数 发病率(%) VAP例数 VAP占比(%) 2014年 33 275 665 2.00 66 9.92 2015年 38 488 624 1.62 79 12.66 2016年 45 320 528 1.17 85 16.10 2017年 51 478 236 0.46 100 42.37 2018年 63 421 163 0.26 136 83.44 2019年 71 918 155 0.22 148 95.48 2020年 68 941 149 0.22 139 93.29 2021年 89 021 161 0.18 158 98.14 2022年 98 105 142 0.14 137 96.48 2023年 116 278 111 0.10 110 99.10 合计 676 245 2 934 0.43 1 158 39.47 χ2 4 396.50 1 735.20 P <0.001 <0.001 2.3 各科室POP发病率

POP发病率居前三位的科室分别为心脏大血管外科(5.277%)、神经外科(2.114%)和胸外科(1.130%)。各科室POP发病率比较,差异有统计学意义(χ2=6 970.90,P<0.001)。见表 3。

表 3 2014—2023年各科室POP发生情况Table 3 Occurrence of POP in each department, 2014-2023科室 手术例次数 POP例次数 发病率(%) 心脏大血管外科 19 575 1 033 5.277 神经外科 26 067 551 2.114 胸外科 38 933 440 1.130 神经内科 2 734 17 0.622 肝胆中心 36 955 179 0.484 老年科 21 806 101 0.463 肾内科 4 297 18 0.419 普外科 101 964 354 0.347 介入放射科 6 571 17 0.259 骨科 56 034 88 0.157 泌尿外科 48 215 50 0.104 整形烧伤科病区 6 463 5 0.077 消化科 23 018 13 0.056 耳鼻咽喉科 29 080 16 0.055 心血管内科 31 326 17 0.054 产科 36 903 18 0.049 妇科 33 926 7 0.021 乳腺病科 39 443 3 0.008 眼科 78 962 2 0.003 其他科室 33 973 5 0.015 合计 676 245 2 934 0.434 2.4 POP感染病原体分布

2 934例次POP患者,共分离感染病原体2 404株。其中革兰阴性(G-)菌占77.58%,居前三位的分别为鲍不动杆菌(29.49%)、肺炎克雷伯菌(22.46%)、铜绿假单胞菌243株(10.11%);革兰阳性(G+)菌占8.53%,主要为金黄色葡萄球菌(7.70%);真菌占13.89%,主要为白念珠菌(8.86%)。见表 4。

表 4 2014—2023年POP感染病原体分布Table 4 Pathogen distribution of POP, 2014-2023病原体 株数 构成比(%) G-菌 1 865 77.58 鲍曼不动杆菌 709 29.49 肺炎克雷伯菌 540 22.46 铜绿假单胞菌 243 10.11 嗜麦芽窄食单胞菌 83 3.45 阴沟肠杆菌 62 2.58 大肠埃希菌 59 2.45 黏质沙雷菌 48 2.00 其他克雷伯菌 12 0.50 其他假单胞菌 35 1.46 其他不动杆菌 22 0.92 其他G-菌 52 2.16 G+菌 205 8.53 金黄色葡萄球菌 185 7.70 其他葡萄球菌 12 0.50 链球菌 8 0.33 真菌 334 13.89 白念珠菌 213 8.86 光滑念珠菌 58 2.41 热带念珠菌 35 1.46 其他念珠菌 13 0.54 其他真菌 15 0.62 合计 2 404 100 2.5 POP发生时间分布

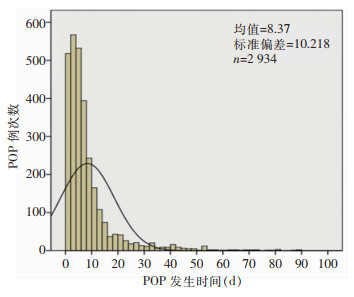

2 934例次POP,51.19% (1 502例次)发生在术后1~5 d,65.81%(1 931例次)发生在术后7 d内,78.80%(2 312例次)发生在手术后10 d内,91.51%(2 685例次)发生在术后20 d内,95.64%(2 806例次)发生在术后30 d内,仅有4.36%(128例次)发生在术后30 d后。见图 1。

3. 讨论

本研究发现2014—2023年该院患者POP发病率为0.10%~2.00%,与国内外研究[11-14]结果基本一致。整体趋势分析显示,POP发病率呈明显下降趋势,可能与临床中对于快速康复外科(fast-track surgery, FTS)的应用增多有关。FTS理念[15-16]由丹麦外科医生Kehlet提出,通过多模式、跨学科的临床路径对患者医疗流程进行标准化,从而改善外科患者手术结局[17],在许多的手术患者中进行研究并取得了很好的效果。随着FTS理念的推广,近年来医疗机构的应用也随之增多;国内外多项研究[18-20]表明,FTS可以缩短手术患者置管时间、住院日数,促进术后心肺功能的恢复,降低术后并发症。本研究结果显示,2014—2023年手术患者POP中VAP占39.47%,与朱明华等[21]研究结果相近;整体趋势分析显示,POP中VAP占比呈上升趋势。随着医学技术的不断发展和进步,临床中FTS和机械通气的使用率逐年升高,使得POP的发病率降低[18-20],POP中VAP占比增加[22],非VAP占比明显降低。提示随着非VAP POP几乎不发生的情况下(2023年仅占0.90%),后续POP的防控应重点关注术后VAP。

POP目前是手术患者中第三大常见并发症,其发病率因手术专科的不同而不同[23]。本研究发现POP大多分布在外科,其中心脏大血管外科最高,其次是神经外科和胸外科,这与国内相关研究[12-13]结果一致。心脏大血管外科POP发病率为5.277%,低于国外9.96%的发病率[24],但高于国内发病率2.91%的研究结果[12]。POP发病率居前三位的科室共同特点包括创伤大、手术时间长、失血多,易对患者免疫功能造成较大破坏,易发生术后感染。此外,各科室的特点也是POP发生高的原因。心脏外科患者体外循环可引起肺部缺血再灌注损伤和系统性炎症反应,且这种损伤随着体循环时间的延长而明显加重[25]。神经外科常伴有不同程度意识障碍甚至长期昏迷,导致咳嗽、吞咽反射减弱甚至消失,增加误吸风险,消化液反流导致消化道细菌移位定植口咽部,定植菌可通过误吸或吸痰等带入下呼吸道造成感染[26]。胸外科患者常因胸部切口疼痛,术后由胸式呼吸改为腹式呼吸,一旦手术切口出现剧烈的疼痛极易引发患者膈肌反射性抑制,导致持续的低潮气量,并伴随患者功能残气量降低,导致肺不张或下肺活动度减小,发生气道分泌物潴留,从而容易导致肺部感染[27]。

本研究结果显示,POP病原体主要是革兰阴性菌,其次是真菌,革兰阳性菌相对较少。革兰阴性菌主要包括鲍曼不动杆菌、肺炎克雷伯菌和铜绿假单胞菌,与国内外相关研究[13, 28-29]结果相似。以上3种细菌均为条件致病菌,常见于医院环境、患者皮肤和口咽部;手术破坏了机体皮肤和组织的完整性,即患者的第一道免疫防线,为这些细菌感染提供了机会。目前POP的定义存在争议,主要集中在术后多长时间的新发肺炎归为POP。有研究将POP定义为外科手术患者在术后30 d内新发的肺炎,若30 d内出院则仍然要追踪到术后第30 d[10, 29-30];也有研究将POP定义为外科手术结束到出院期间发生的肺炎[31]。本研究显示65.81%POP发生在术后7 d内,78.80%发生在手术后10 d内,而仅有4.36%发生在术后30 d后。因此,POP预防的关键时间是术后10 d内。本研究也存在一定局限性,因为实际情况并没有随访,可能漏掉部分发生在出院后至术后30 d内POP,导致本研究的数据比真实情况略低。有条件的医疗机构后续可以开展相关的随访工作,获取更准确的POP数据。

综上所述,POP发病率呈下降趋势,其中VAP患者应作为后续改进工作的重点关注对象,心脏血管外科、神经外科和胸外科则是POP的重点关注科室,手术后10 d内应作为POP的重点关注时间段。

利益冲突:所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突。

-

表 1 2014—2023年2 934例POP患者基本情况

Table 1 Basic information of 2 934 POP patients, 2014-2023

基本情况 患者例数 构成比(%) 年龄(岁) <50 615 20.96 50~59 573 19.53 60~69 914 31.15 ≥70 832 28.36 性别 男性 2 012 68.58 女性 922 31.42 手术方式 急诊 723 24.64 择期 2 211 75.36 NNIS风险指数(分) 0 577 19.67 1 1 297 44.20 2 1 045 35.62 3 15 0.51 表 2 2014—2023年POP发病率及VAP占比

Table 2 Changing trend of POP incidence and proportion of VAP, 2014-2023

年份 手术例次数 POP例次数 发病率(%) VAP例数 VAP占比(%) 2014年 33 275 665 2.00 66 9.92 2015年 38 488 624 1.62 79 12.66 2016年 45 320 528 1.17 85 16.10 2017年 51 478 236 0.46 100 42.37 2018年 63 421 163 0.26 136 83.44 2019年 71 918 155 0.22 148 95.48 2020年 68 941 149 0.22 139 93.29 2021年 89 021 161 0.18 158 98.14 2022年 98 105 142 0.14 137 96.48 2023年 116 278 111 0.10 110 99.10 合计 676 245 2 934 0.43 1 158 39.47 χ2 4 396.50 1 735.20 P <0.001 <0.001 表 3 2014—2023年各科室POP发生情况

Table 3 Occurrence of POP in each department, 2014-2023

科室 手术例次数 POP例次数 发病率(%) 心脏大血管外科 19 575 1 033 5.277 神经外科 26 067 551 2.114 胸外科 38 933 440 1.130 神经内科 2 734 17 0.622 肝胆中心 36 955 179 0.484 老年科 21 806 101 0.463 肾内科 4 297 18 0.419 普外科 101 964 354 0.347 介入放射科 6 571 17 0.259 骨科 56 034 88 0.157 泌尿外科 48 215 50 0.104 整形烧伤科病区 6 463 5 0.077 消化科 23 018 13 0.056 耳鼻咽喉科 29 080 16 0.055 心血管内科 31 326 17 0.054 产科 36 903 18 0.049 妇科 33 926 7 0.021 乳腺病科 39 443 3 0.008 眼科 78 962 2 0.003 其他科室 33 973 5 0.015 合计 676 245 2 934 0.434 表 4 2014—2023年POP感染病原体分布

Table 4 Pathogen distribution of POP, 2014-2023

病原体 株数 构成比(%) G-菌 1 865 77.58 鲍曼不动杆菌 709 29.49 肺炎克雷伯菌 540 22.46 铜绿假单胞菌 243 10.11 嗜麦芽窄食单胞菌 83 3.45 阴沟肠杆菌 62 2.58 大肠埃希菌 59 2.45 黏质沙雷菌 48 2.00 其他克雷伯菌 12 0.50 其他假单胞菌 35 1.46 其他不动杆菌 22 0.92 其他G-菌 52 2.16 G+菌 205 8.53 金黄色葡萄球菌 185 7.70 其他葡萄球菌 12 0.50 链球菌 8 0.33 真菌 334 13.89 白念珠菌 213 8.86 光滑念珠菌 58 2.41 热带念珠菌 35 1.46 其他念珠菌 13 0.54 其他真菌 15 0.62 合计 2 404 100 -

[1] Fujita T, Sakurai K. Multivariate analysis of risk factors for postoperative pneumonia[J]. Am J Surg, 1995, 169(3): 304-307. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(99)80163-9 [2] Xiang BB, Jiao SL, Si YY, et al. Risk factors for postoperative pneumonia: a case-control study[J]. Front Public Health, 2022, 10: 913897. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.913897 [3] Chughtai M, Gwam CU, Mohamed N, et al. The epidemiology and risk factors for postoperative pneumonia[J]. J Clin Med Res, 2017, 9(6): 466-475. doi: 10.14740/jocmr3002w [4] 姚尧, 查筑红, 李家丽, 等. 基于AHP-风险矩阵构建手术后肺炎风险评估模型研究[J]. 中国感染控制杂志, 2023, 22(11): 1312-1318. doi: 10.12138/j.issn.1671-9638.20234298 Yao Y, Zha ZH, Li JL, et al. Risk assessment system of postoperative pneumonia based on AHP and risk matrix[J]. Chinese Journal of Infection Control, 2023, 22(11): 1312-1318. doi: 10.12138/j.issn.1671-9638.20234298 [5] 肖科, 曹汴川, 黄富礼, 等. 破伤风患者合并医院获得性肺炎的危险因素及病原菌[J]. 中国感染控制杂志, 2020, 19(6): 559-563. Xiao K, Cao BC, Huang FL, et al. Risk factors and pathogen distribution of hospital-acquired pneumonia in patients with tetanus[J]. Chinese Journal of Infection Control, 2020, 19(6): 559-563. [6] 罗斌华, 徐斯勰, 陈苾, 等. 外科患者手术后医院感染直接经济损失评价[J]. 中国感染控制杂志, 2020, 19(12): 1070-1075. doi: 10.12138/j.issn.1671-9638.20206168 Luo BH, Xu SX, Chen B, et al. Direct economic loss due to postoperative healthcare-associated infection in surgical patients[J]. Chinese Journal of Infection Control, 2020, 19(12): 1070-1075. doi: 10.12138/j.issn.1671-9638.20206168 [7] 赵霞, 王力红, 魏楠, 等. 老年患者医院获得性肺炎风险评估模型的构建[J]. 中国感染与化疗杂志, 2020, 20(3): 271-276. Zhao X, Wang LH, Wei N, et al. Construction of risk assessment model of hospital-acquired pneumonia in elderly patients[J]. Chinese Journal of Infection and Chemotherapy, 2020, 20(3): 271-276. [8] 王雪, 陈赛赛, 孙跃娟, 等. 颈髓损伤术后医院获得性肺炎影响因素及PCT与CRP的诊断价值[J]. 中华医院感染学杂志, 2021, 31(6): 891-895. Wang X, Chen SS, Sun YJ, et al. Influencing factors for nosocomial pneumonia after cervical spinal cord injury and diagnostic value of PCT, CRP[J]. Chinese Journal of Nosocomiology, 2021, 31(6): 891-895. [9] 中华人民共和国卫生部. 医院感染诊断标准(试行)[J]. 中华医学杂志, 2001, 81(5): 314-320. Ministry of Health of the People's Republic of China. Diagnostic criteria for nosocomial infections(Proposed)[J]. National Medical Journal of China, 2001, 81(5): 314-320. [10] 中华预防医学会医院感染控制分会第四届委员会重点部位感染防控学组. 术后肺炎预防和控制专家共识[J]. 中华临床感染病杂志, 2018, 11(1): 11-19. The Fourth Committee of the Hospital Infection Control Branch of the Chinese Preventive Medicine Association Focused on the Infection Prevention and Control Group. Expert consensus on prevention and control of postoperative pneumonia[J]. Chinese Journal of Clinical Infectious Diseases, 2018, 11(1): 11-19. [11] Metersky ML, Wang Y, Klompas M, et al. Temporal trends in postoperative and ventilator-associated pneumonia in the United States[J]. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol, 2023, 44(8): 1247-1254. doi: 10.1017/ice.2022.264 [12] 姚尧, 查筑红, 罗光英, 等. 一所三级综合教学医院外科科室手术后肺炎风险评估[J]. 中国感染控制杂志, 2024, 23(2): 214-219. Yao Y, Zha ZH, Luo GY, et al. Risk assessment on postoperative pneumonia in the surgical department of a tertiary comprehensive teaching hospital[J]. Chinese Journal of Infection Control, 2024, 23(2): 214-219. [13] 周嘉祥, 贾建侠, 赵秀莉, 等. 某三级甲等综合性医院外科术后肺炎流行病学调查[J]. 中国感染控制杂志, 2020, 19(5): 451-456. Zhou JX, Jia JX, Zhao XL, et al. Epidemiological investigation on postoperative pneumonia in a tertiary first-class hospital[J]. Chinese Journal of Infection Control, 2020, 19(5): 451-456. [14] 周珏, 张贤平, 姜亦虹. 不同手术时机患者术后肺部感染情况[J]. 中国感染控制杂志, 2017, 16(3): 237-239. Zhou J, Zhang XP, Jiang YH. Postoperative pulmonary infection in patients undergoing surgical operation at different surgical opportunities[J]. Chinese Journal of Infection Control, 2017, 16(3): 237-239. [15] Wilmore DW, Kehlet H. Management of patients in fast track surgery[J]. BMJ, 2001, 322(7284): 473-476. [16] Kehlet H, Wilmore DW. Multimodal strategies to improve surgical outcome[J]. Am J Surg, 2002, 183(6): 630-641. [17] 杨雪梅, 倪钊, 任玉英, 等. 应用快速康复理念优化心脏介入围术期流呈对桡动脉支架植入术后患者康复影响的随机对照试验[J]. 中国胸心血管外科临床杂志, 2019, 26(4): 364-368. Yang XM, Ni Z, Ren YY, et al. Influence of applying fast-track surgery to optimize the process in perioperative period of cardiac intervention on rehabilitation of patients with radial artery stenting surgery: a randomized controlled trial[J]. Chinese Journal of Clinical Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, 2019, 26(4): 364-368. [18] 胡伟, 管玉珍. 围术期快速康复外科理念在老年心脏外科手术患者中的应用[J]. 中国老年学杂志, 2022, 42(9): 2178-2180. Hu W, Guan YZ. Application of perioperative fast track surgery in elderly patients undergoing cardiac surgery[J]. Chinese Journal of Gerontology, 2022, 42(9): 2178-2180. [19] 张玉江, 周军, 阿合提别克, 等. 快速康复外科理念在新辅助化疗联合腹腔镜下胃癌D2根治术治疗进展期胃癌中的应用[J]. 中华实用诊断与治疗杂志, 2018, 32(5): 467-470. Zhang YJ, Zhou J, A Htbk, et al. Fast-track surgery in neoadjuvant chemotherapy combined with laparoscopic D2 radical gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer[J]. Journal of Chinese Practical Diagnosis and Therapy, 2018, 32(5): 467-470. [20] Le Guen M, Cholley B, Fischler M. New fast-track concepts in thoracic surgery: anesthetic implications[J]. Curr Anesthesiol Rep, 2016, 6(2): 117-124. [21] 朱明华, 方玲, 刘英杰, 等. 急诊手术患者发生医院获得性肺炎与呼吸机相关肺炎的危险因素[J]. 中国感染控制杂志, 2018, 17(8): 702-707. Zhu MH, Fang L, Liu YJ, et al. Risk factors for hospital-acquired pneumonia and ventilator-associated pneumonia in patients undergoing emergency surgery[J]. Chinese Journal of Infection Control, 2018, 17(8): 702-707. [22] Perren A, Brochard L. Managing the apparent and hidden difficulties of weaning from mechanical ventilation[J]. Intensive Care Med, 2013, 39(11): 1885-1895. http://www.onacademic.com/detail/journal_1000035932334410_9c96.html [23] Chughtai M, Gwam CU, Khlopas A, et al. The incidence of postoperative pneumonia in various surgical subspecialties: a dual database analysis[J]. Surg Technol Int, 2017, 30: 45-51. [24] Wang DS, Huang XF, Wang HF, et al. Risk factors for postoperative pneumonia after cardiac surgery: a prediction model[J]. J Thorac Dis, 2021, 13(4): 2351-2362. [25] Tanner TG, Colvin MO. Pulmonary complications of cardiac surgery[J]. Lung, 2020, 198(6): 889-896. [26] 罗文娟, 李兰兰, 张影华, 等. 开颅手术患者手术后肺炎的危险因素[J]. 中国感染控制杂志, 2019, 18(4): 300-304. Luo WJ, Li LL, Zhang YH, et al. Risk factors for postoperative pneumonia in patients undergoing craniotomy[J]. Chinese Journal of Infection Control, 2019, 18(4): 300-304. [27] 许缤, 陈红岩, 孙嫣, 等. 胸外科手术后医院获得性肺炎危险因素分析[J]. 中华医院感染学杂志, 2012, 22(1): 64-66. Xu B, Chen HY, Sun Y, et al. Risk factors of hospital-acquired pneumonia after thoracic surgery[J]. Chinese Journal of Nosocomiology, 2012, 22(1): 64-66. [28] 文细毛, 任南, 吴安华, 等. 2016年全国医院感染监测网手术后下呼吸道感染现患率调查[J]. 中国感染控制杂志, 2018, 17(8): 653-659. Wen XM, Ren N, Wu AH, et al. Prevalence rates of postope- rative lower respiratory tract infection of national healthcare-associated surveillance network in 2016[J]. Chinese Journal of Infection Control, 2018, 17(8): 653-659. [29] Simonsen DF, Søgaard M, Bozi I, et al. Risk factors for postoperative pneumonia after lung cancer surgery and impact of pneumonia on survival[J]. Respir Med, 2015, 109(10): 1340-1346. [30] Hiramatsu T, Sugiyama M, Kuwabara S, et al. Effectiveness of an outpatient preoperative care bundle in preventing postoperative pneumonia among esophageal cancer patients[J]. Am J Infect Control, 2014, 42(4): 385-388. [31] Chen P, A YJ, Hu ZQ, et al. Risk factors and bacterial spectrum for pneumonia after abdominal surgery in elderly Chinese patients[J]. Arch Gerontol Geriatr, 2014, 59(1): 186-189.

下载:

下载: